It’s been four months since I last provided an update on our progress in building our new scoring application, so I thought it was about time to lift the curtain a little bit and give you some idea about what we’ve been working on. Warning: this post is pretty nerdy, and very long… and it only covers April and May.

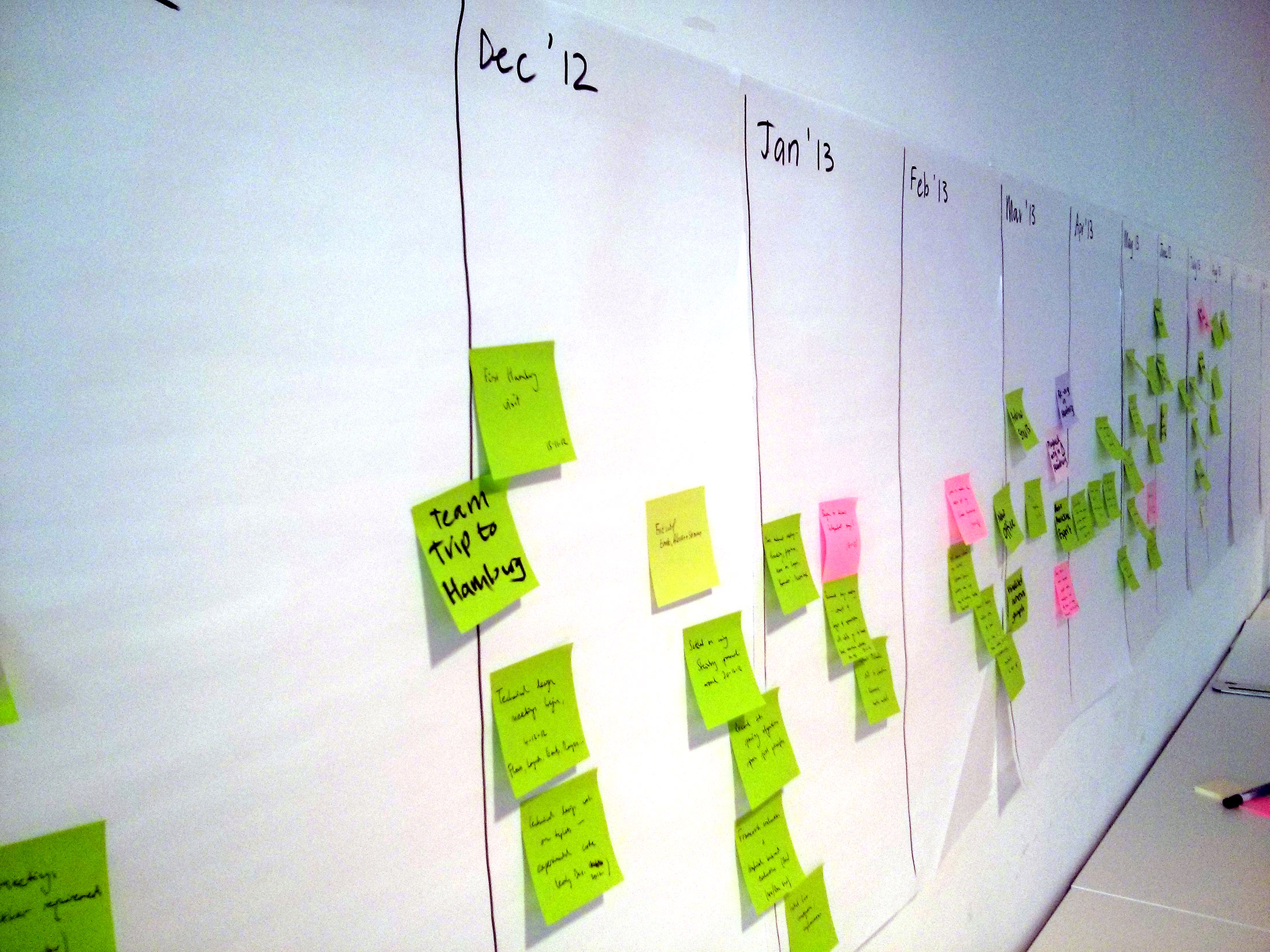

The image above is our project timeline, which we update every two weeks at our sprint review meetings. For those of you not familiar with software development methodology, Steinberg uses agile development, which is based around short spans of work (our team uses two weeks, and other teams within Steinberg use four) with an emphasis on achieving measurable progress in that time. The sprint review meeting at the end of each iteration serves both as a forum to share what we’ve been working on, including a little bit of show and tell where possible, and to plan the next sprint. As the meeting goes along, we write down any milestones we’ve reached during that sprint, and put them up on the timeline (good things are green, obstacles or impediments are pink — fortunately there have been relatively few of the latter, so far). Our timeline is now nine months long, and lots of good stuff has been happening.

April

The biggest event in any given April for a company like Steinberg is Musikmesse, the huge trade show that takes place in Frankfurt every spring. I was fortunate enough to attend the show for a couple of days, and filled those days talking to interesting folks working in our field, including Michael Good of MusicXML fame, Joe Berkovitz of Noteflight, Dominik Hörnel of Scorio, Thomas Bonte of MuseScore, Yair Lavi of Tonara, Bob Hamblok and Jonas Coomans of NeoScores, and others besides.

I came away from the show energised by what I had seen and full of ideas about how our new application might fit into this ecosystem of interesting companies all coming at the intersection of music notation and technology from different angles.

Of course, the Steinberg booth was packed every day, and the show attendees were wowed by the new products on display, in particular Wavelab 8, which was launched at the show, and Cubasis for iPad, not to mention the continued excitement around Cubase 7, released a few months before.

Later in the month, we had a visit from an expert SCORE engraver, Simon Smith, who works for Boosey and Hawkes in London and Éditions Durand in Paris. We wanted to see first-hand the strengths and weaknesses of SCORE’s almost entirely graphical (rather than semantic) approach towards score production. Simon skilfully entered a system of polymetric music from a score by Thomas Adès in a matter of minutes, demonstrating both how quick the text-based entry method of SCORE can be once you become proficient with it, and one of SCORE’s secret weapons: being able to space any rhythmic item as if it has a different duration than its notated duration (e.g. to space a dotted half note as if it were a quarter note, and so on).

Our aim with our new application is to produce a tool capable of the same kind of flexibility that SCORE’s graphics-based approach allows without compromising on the semantic richness that programs like Finale and Sibelius are built upon — indeed, we aim to go significantly further in semantic terms than current-generation scoring programs.

I also drove out to visit with engraver and publisher Barry Ould, who runs the Bardic Edition imprint, which publishes works by composers as diverse as Sorabji, Busoni and Grainger. Indeed, it’s Grainger who is particularly near and dear to Barry’s heart, as he has been one of the prime movers in The Percy Grainger Society, which seeks to promote the works of this under-appreciated Australian composer and performer, and we talked for some time about how he got involved — which is an interesting story that will have to wait for another day.

My reason for visiting Barry wasn’t to talk Grainger, however. Barry is himself an engraver with several decades of experience, and he has been witness to the seismic technological shifts in how music engraving is performed. He showed me his old Musicwriter modified typewriter, and we talked about the first computer engraving package he used on an early Mac (HB-Engraver from HB-Imaging), and so on. Barry was also an extensive user of Not-a-set dry transfer sheets, which he used to augment the limited output produced by his Musicwriter, and he very generously provided me with a number of new sheets that I hadn’t previously seen, all of which are useful models for symbol design in Bravura, our new music font.

I was also very fortunate to receive some further sheets from an editor and engraver for G. Schirmer, Peter Cressy, who took the time to package up some sheets and send them to me all the way from Vermont for me to scan and return to him. Thank you, Barry, and thank you, Peter.

May

In May, I presented my work to date on the Standard Music Font Layout initiative at the Music Encoding Conference in Mainz, Germany. I wrote about SMuFL and the Bravura font at the time, but things have progressed enormously since then — indeed, it’s the main thing I’ve personally been working on since I returned from Germany at the end of the month.

The announcement of SMuFL seemed to strike a chord, and I got a flood of feedback. A community of software developers, engravers and even a couple of font developers immediately started discussing the standard, suggesting new symbols to be added, debating various technical issues about the use of particular font features, and so on.

The upshot of all this discussion is that since the initial release of SMuFL on 23 May, there have been two further major revisions, which have between them expanded the repertoire of symbols in the standard from just over 800 to around 1700 in the current release at the time of writing, SMuFL 0.6.

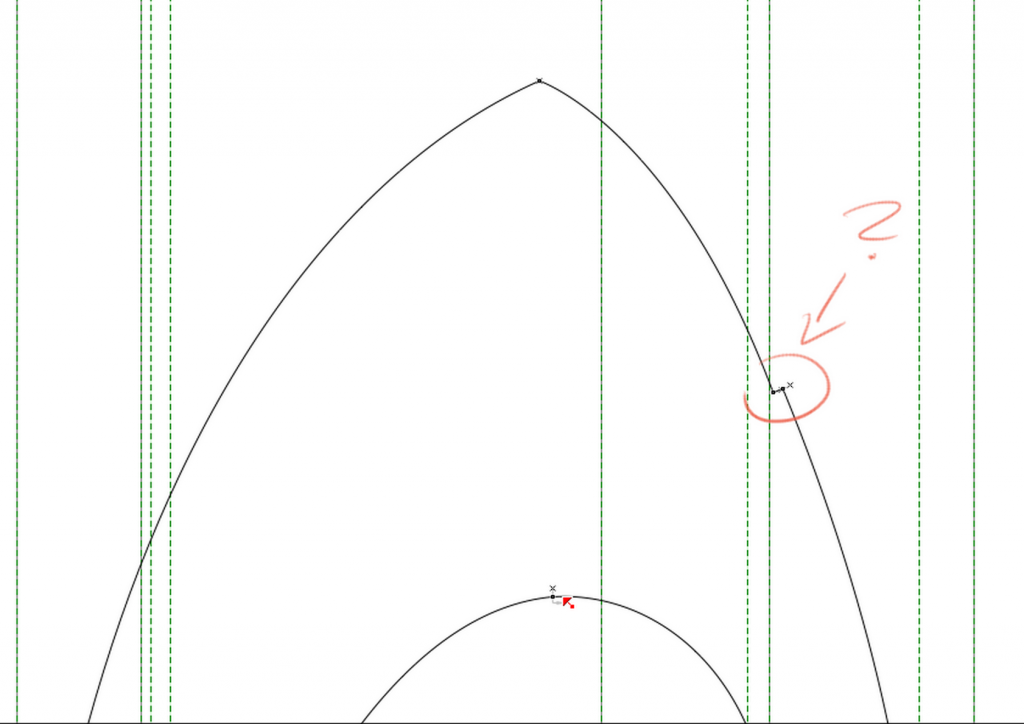

The Bravura font has likewise been updated in step with the expansion of SMuFL, and a number of minor technical problems with the font have been fixed. For example, several people were eagle-eyed enough to spot a peculiar kink in the outline of the G clef, which was undetectable except at very high magnification:

Here are a couple of my favourite new glyphs that have been added to Bravura since the initial release in May:

Hundreds of new symbols have been added, including the complete set of Sagittal microtonal accidentals, thanks to the help of Sagittal’s creators George Secor and Dave Keenan, ranges of wiggly lines of various shapes and sizes (thanks to Emil Wojtacki for help with those), pictograms for electronic music (such as volume faders, transport controls, etc.), further instrumental techniques, and many more besides.

While I have been beavering away on SMuFL and Bravura, the rest of the team has continued to build up the foundations of our new application. Our test harness, which exercises the underlying music model, can now display barlines, which may not sound like much, but in fact it’s quite a significant step, because bars are by no means the fundamental structural container in our model that they are in other scoring programs, and this has the potential to unlock all sorts of sophisticated functionality. The test harness can also save files in the beginnings of our application’s native file format, in addition to being able to export rudimentary MusicXML.

Finally, inspired both by the previous month’s visit by SCORE engraver Simon Smith, and by a couple of talks at the Music Encoding Conference about Plaine & Easie Code, an extraordinarily long-lived text-based encoding for musical incipits widely used by libraries and other academic research projects, I began to think about the step-time input method for our application in the light of translating the keystrokes you would use to input music interactively into strings of text that could be processed in a single operation, effectively providing something a little like the text-based input method of SCORE (and other similar programs, such as Lilypond, and formats, such as ABC).

By looking at an excerpt of music and typing out the keystrokes that would be needed to input that music in our application, I could start to get a feel for how inputting music directly into our application will work. I’ll share one little tidbit to give you an insight into the design process: should accidentals be specified before or after the pitch name when inputting notes from the computer keyboard? There are pros and cons to either approach, but in the end we decided that you should specify the accidental before the pitch name so that you’re not forced to hear the wrong note before you can tell the software you want to apply an accidental. This same principle also applies to things like specifying the octave of the note you’re about to input.

This post is already quite long enough, so you’ll have to wait for the next instalment of this developer diary to find out more — but I promise I won’t make you wait another four months to read it. We love to read your comments, so please feel free to share your thoughts below.

Very interesting post (I think I am nerdy myself!). Especially this part : “bars are by no means the fundamental structural container in our model that they are in other scoring programs, and this has the potential to unlock all sorts of sophisticated functionality.”

So this means we may be able to make trans-barline tuplets? I have been asked to find a workaround for this on Sibelius. It was quite easy to do it, but to do it “naturally” would be even better.

Can’t wait to see these “sophisticated functionalities”…

Lilypond has never been affected by such arbitrary restrictions as “bars” — trans-barline (and, indeed, trans-system) tuplets are no problem. if you want “sophisticated functionalities”, you should check out Lilypond.

Hum, have you checked the credits? I worked on Lilypond for translation of music terms. Yes, LIlypond does not have the bar limitations as Sibelius, for instance, but the Scheme-like syntax for programming the thing (beside entering easy simple notes) is, for the least, tedious. It gets awful when you’re not okay with the choices of Lilypond for layout. We are not talking about separate parts, etc.

I dropped Lilypond because of lack of time. I was struggling for a month to enter a simple alto/double bass/piano piece. I returned to Sibelius and entered it in an hour. So for now on, I strongly believe in WYSIWYG for a notation software.

Interesting… I find it much faster to enter music in Lilypond than in Finale (which I used for almost 15 years) or Sibelius (which, admittedly, I only used for about 2 years). Hopefully, you will find this new application being developed here more to your liking and needs.

Thank you, and all the team, for all you’re doing.

I’m with the above! What is the fundamental container unit? (I can definitely see why you wouldn’t want it to be a bar!)

M’kay!

“Should accidentals be specified before or after the pitch name when inputting notes from the computer keyboard?”

Could the users do either according to their preference? People coming from Sibelius will be used to typing the accidental first, but if they came from Finale and used Simple Entry a lot, then they’ll probably try placing the notes first and then modifying them. Typing all the modifiers and then typing the note is probably the superior method, but if you allow both methods then some of your users won’t have to retrain themselves.

@Jordan: I think it’s important up-front to know that our new application won’t work like either Sibelius or Finale, and folks who are using either of those applications (or indeed any other scoring application) had better expect a certain amount of retraining if they want to use our new application. We have the freedom to come up with a new, and hopefully better, way of handling note input and indeed practically every other aspect of a scoring application, and in my view we should have the courage of our convictions and follow that through to its fullest extent — which means no compatibility options to make our new application work like another old application.

This sounds both scary and exciting.

I’m not fully certain I have understood the upcoming music input by keys yet, but if it is like Bb8, A##16, Ebb1 etc I would prefer accidentals as well as duration after the ‘main pitch’. ##A16 is closer to how it would look on screen and paper though. I guess I could re-learn. The important thing is that it is fast and close on the keyboard (i.e. NOT using the keypad). There is prob a lot to be adapted from other keyboard input engraving systems. Daniel, have you checked the input system on the excellent Amadeus system?

Regards

Mats

@Mats: I’m somewhat familiar with the input method in Amadeus, though not from first-hand experience (I have seen the manual, but not the program itself), but I’m sure it’s generically similar to the input methods of SCORE, Amadeus and Lilypond, i.e. based around the program parsing a string of text commands. To be clear, though, I’m not proposing that this should be the main way people input music into our application, but it might be useful for e.g. accelerating the input of music via a Lua script.

as long as there is a feature such as typing a-b-c to get a-b-c… so we can alo type the last page of our string quartet on the train, without external keyboard and too many movement as to use a mouse. (p-p-please)

– did ya fellows consider Input through singing?

hand (= have a nice day)

Juan María

( Album Tango Monologues )

@Juan Maria: Don’t worry, alphabetic input of pitches by their letter names is something you can be fairly certain of. You might find our choice of which keys determine note duration more controversial, but I will save that information for another day!

It also sounds a little like the old Sibelius approach to life… this is how we do it, so get used to the idea. Shouldn’t Jordan’s suggestion of flexibility of approach (such as the way preferences can be chosen by the user in InDesign, for example) be built into this new software when it provides so many other opportunities to be new and different?

@Brian: Oh, you know how to push my buttons! I’ll try not to take the bait on the whole “it’s Sibelius’s way or the highway” thing, which I heard countless times over the years and which was always unfounded. What I will say is this: it’s important that people who design software are opinionated and decisive. Software whose designers are indecisive are full of options; to paraphrase Joel Spolsky, every checkbox you see in an application represents a decision the designer failed to make. But equally importantly, I am a believer in Paul Saffo’s mantra of “strong opinions, weakly held“, and if I’m wrong about how note input feels in our new application once we’ve actually implemented it, then I’ll be only too happy for the team to change it.

I leave you with this thought: how do you expect us to make software that is “new and different” if we spend all our time adding options to make the application the same as old applications?

If you’re going in something like a score input scheme, that would be wonderful. Also, I’m sure you have been exploring the connections to braille music notation.

But most exciting are your directions towards barline-less scores. With the right historical fonts, you could easily come up with incipits for medieval and Renaissance pieces, or even diplomatic facsimiles. One suggestion – ligature shapes could be incorporated rather simply into a dialog box or menu similar to Sibelius’ lines (L), acting like simple lines and boxes, with an option to fill them in. New notational symbols could be created this way.

Daniel,

Warning: off topic.

This is my first chance to respond to you.

I asked you once before about easy to edit midi CC information, to control instrument performances… and you said it was something that may happen down the road. This isn’t some “side feature”, it’s the primary way to control the performance of any and every virtual instrument from every last sample company out there.

To me, this sounds like Steinberg is trying to make a new notation program just like the programs that have come before and gone.

If you alienate the same crowd Sibelius and Finale have always ignored, this software will fail. Frankly, I expect more from Steinberg. I still have hope and I wish you and the development team well. Please just don’t ignore those of us who want to work in notation, but have to control the midi performance. We’re not exactly a small crowd. I don’t think I’m asking a lot for a program I and many others would be forking out a lot of money for.

While I am frustrated by this you and your team have my fullest respect. I just don’t want a repeat of the same problem I’ve seen in every notation software to date. I can’t afford to fork out money for a program just cause it has a shiny new font.

@Sean: A big project like our new scoring application will involve lots of trade-offs. We have a list of requirements a mile long, and we won’t be able to address every single one of them in the first version of our application. Hopefully, the first version of our application will represent the start of our journey, rather than the end: there will be further updates that add more functionality over time. At the moment, I can’t make any promises whether any specific feature or workflow will be included in the first version of our program, because it’s too early to say. But please be assured that we do understand the need for detailed control of playback parameters in our application, and I’m sure we will address it: I just can’t give you any promises right now as to when it will be.

Daniel,

1) I believe that’s completely fair.

I suggest, however unlikely, publishing a road-map of planned features around release time. I’d buy v1.0 to support development if some features were at least “on the plan” for v2.

2) Do you guys have a vague goal for release? I know this is extremely early still, but late 2014, early 2015, 2077?

@Sean: I can’t provide any guesses about our release date at this point, I’m afraid, but it will be a while: we are still at the early stages of development.

for me the move of the Sibelius programming team to Steinberg is a great opportunity to merge the outstanding MIDI controller features which have been present in Cubase for the best part of two decades with an advanced, user-friendly notation interface. If the playback control is not improved from Sibelius then I’m not sure that there will be any pressing reason to upgrade. Those of us who are unlikely to ever see large scale orchestral works ever performed by a real orchestra (and surely that is the majority!) would really like to have everything in one software application. In my view the more advanced audio features of Cubase are not necessary (I don’t understand how to use them anyway…) but a simple editor along the lines of the Cubase Key editor would probably be sufficient, together with more intelligent versions of the performance presets in Sibelius.

David

Interesting read. Sounding very interesting. Thanks for this Daniel.

As a longtime Score user (only gave it up when the publishers I worked with switched to Sibelius, which I still use in Version 6), my only worry is it took just about 3 years of regular use with Score to “memorize” just about everything it took to use the program efficiently. That was a long slog, and I was 20 years younger then. I use Sibelius as both and engraving and a composing tool; when I’m engraving, it’s about speed and accuracy. When I’m writing, I often like the slower process of note-by-note entry; it slows me down and forces me to think more carefully about what I’m doing. Thanks for the update–looking forward to the new program down the line!

Thanks, Daniel! I for one am eagerly looking forward to what you all are creating!! Best regards, Bettie

Great stuff, good luck with everything Daniel.

Hello,

I’m the moderator for Yahoo’s tuning list, found at http://groups.yahoo.com/group/tuning, which focuses on alternative tunings (often called “microtonal” tunings). I also administer Facebook’s “Xenharmonic Alliance” group, a counterpart to the list, found at https://www.facebook.com/groups/xenharmonic2/. We’re overjoyed to see that you’ve decided to implement Sagittal!

We believe that our community has a powerful contribution to make to 21st century music. Yet, though the overall size of group is very large, far too often we’ve been ignored by the music software community, leaving us with a dearth of tools we need to actually make music. This in turn causes us to make less music, turns newcomers off from the community, which finally causes us to be ignored more by major software developers, in a vicious circle. That you’ve taken the initiative to give us a major piece of software with Sagittal support is a huge step forward for us, and we’re very excited about this!

The question on everyone’s mind is: do you intend to implement microtonal playback support as well?

The microtonal community would be elated if there existed even a cursory, easy-to-implement, workable solution for us to actually hear our scores played back in the tunings which we’ve composed them in. It would be a huge advancement for our group to have even something which only solves the problem halfway, but which integrates in a larger workflow with other tools that we currently use to arrive at the solution. We recognize that now, in this crucial development phase of this new software, would be a good time to make our voices heard!

I invite you to stop by at the tuning list as well, should you desire any general feedback from our community, as well as clarity on precise mathematical and technical recommendations on which simple things would benefit the most microtonalists. And again, THANK YOU for implementing Sagittal, and enabling the larger microtonal community to finally take a leap forward – we’re all watching this blog very carefully!

Best,

Mike Battaglia

Lots of microtonal activity on the Lilypond list(s).

@Mike: For the avoidance of doubt, please allow me to elaborate on the inclusion of microtonal accidentals such as the Sagittal system within our font, Bravura. Bravura includes a wide variety of symbols for microtonal accidentals (Stein-Zimmermann, Ezra Sims, Extended Helmholtz-Ellis JI Pitch Notation, Xenakis, standard accidentals with arrows, Sims accidentals with arrows, maqam accidentals, plus, of course, Sagittal, and perhaps a couple of other schemes that I’m forgetting at the moment). However, the presence or absence of particular symbols in Bravura shouldn’t be taken as a firm indicator of whether or not a particular kind of notation will be supported in our application, or at least in the first version of our application.

Bravura is intended to have as wide a repertoire of symbols as possible, because in addition to being the primary music font for our new application it is also intended to be a reference font for the SMuFL standard, and hence it must contain every symbol defined in SMuFL, even if that symbol won’t be used directly by our application.

Having said all that, I don’t want to do down the support we are intending to provide for microtonal notation in our application. It will certainly be possible, with minimal fuss, to use arbitrary schemes of accidentals in our application, and in certain scenarios we expect it to be able to produce correct playback by default, too.

Naturally I welcome further input from experts in the field of microtonality. Certainly George and Dave, the creators of Sagittal, have been extremely generous with their time and have provided me with valuable input not only about Sagittal but also about other systems for microtonal notation. Thanks for taking the time to write, Mike!

Very interesting post. Nice to read about the pictograms for electronic music, they’ll come in very handy. Really looking forward to the new program. Best of luck Daniel (and team).

Great to ear that the software is looking at things like polymetrics … would the capabilities also extend to other things such as polytempo??

Your readers may be interested in knowing that Lilypond can do essentially everything SCORE does — including “altered durations” (i.e., “being able to space any rhythmic item as if it has a different duration than its notated duration”) — while being completely free, available on all major OS platforms, and supported by a very active community.

Polymetrics and polytempi are also well-supported in Lilypond: I just finished engraving a song where the piano was often in 7/8 while the singer alternated between several duple meters (e.g., 4/4, 3/4, etc.) and the oboe was in yet a third time signature.

This is only a very small subset of that behaviour, but you might have a look at the score example in this post: http://lilypondblog.org/2013/07/creating-anything-you-can-imagine-with-finale/

It shows the same music in several timing context at the same time, the music entered only once and the different scalings done automatically by LilyPond.

The follow-up post shows how to do that on a larger scale, and there is a third one in the queue demonstrating how to use such text-based techniques to produce a complex score automatically.

@Urs & @Kieren: It’s great to see such passionate advocacy for Lilypond from some of its more vocal users — though I’m not sure this is the most appropriate forum for it. Lilypond, like SCORE, is undoubtedly a great tool for the kind of person who considers learning Scheme and LaTeX no sweat, and it’s undoubtedly very powerful, but I think it’s safe to say that it’s not for everybody (just as our new application will undoubtedly not be for everybody, either). Fortunately, LaTeX and InDesign happily co-exist, and I’m sure our new application and Lilypond will happily co-exist too. If people are interested in Lilypond, they know where to go.

Of course this isn’t a ‘generically’ suited forum for advocating LilyPond.

But I think it’s legitimate to comment on features you plan for your application from the perspective of other programs. And I would equally be interested in comparable comments from e.g. SCORE, Finale or Musescore users.

Daniel – just to correct what you’ve written above – LilyPond is not just “for the kind of person who considers learning Scheme and LaTeX no sweat”. I have created hundreds (possibly thousands) of scores with LilyPond and have no knowledge of either Scheme or LaTeX – just the ability to enter characters into an editor. Its basic syntax and its general ability to “do the right thing” make it perfect for most typesetting.

I’d add that, as a mature music student, I have to use Sibelius for my studies, and many of its features drive me crackers. The main one is its insistence on knowing better that I do what rhythms I’m trying to enter. When I compose, I often change my mind about whether I want a crochet, a quaver or a dotted note. Sibelius’s obsession with keeping the “correct” number of beats in a bar then leave me with unwanted rests, notes I want deleted and all manner of other annoyances. Getting rid of that would make Sibelius much improved, IMHO.

@Phil: I guess you do, in point of fact, now actually have some knowledge of Scheme after producing thousands of pages of music with Lilypond, since (based on my limited understanding of Lilypond) its input format is based on various features of the language. However, I can’t really discuss the finer points of Lilypond here (or indeed anywhere) since I’m not qualified to make any judgements about it. There are lots of benefits to programs that use a text-based input format like Lilypond (indeed, I’m currently drafting bits of user documentation for our new application using Markdown, for similar reasons to those given by Urs in his essay about Lilypond), but they’re not for everybody. If you’re having fun with Lilypond and finding it does the job for you, that’s fantastic. I think you must realise that it’s not for everybody, but I understand this seems like a good forum for you and your fellow lilypond-users list members to bang the drum for your favoured tool.

As for Sibelius’s insistence on keeping the right number of beats in a bar, there are obviously both good and bad things about this. I think everybody would agree that a scoring program should try to prevent you from putting music on the stand with obvious rhythmic errors, such as bars containing the wrong number of beats, but most would probably agree that a bit more flexibility at the input and editing stage would be very useful. As with all things, then, there’s a balance to be struck, and hopefully we will strike it just right with our new application. Time will tell!

Replying to myself: just for the sake of correctness, I have been informed by David Kastrup, one of the lead developers of LilyPond, that in fact LilyPond’s default input syntax does not include any Scheme, but you can easily intersperse Scheme commands into LilyPond input files. I also note that the correct way of rendering LilyPond’s name is using camel case.

As a professional musician in an orchestra that plays quite a bit of new orchestral music, I have a few thoughts on this idea of allowing composers the freedom to adjust the number of beats in a bar. When faced with a new piece on the stand in front of us occasionally there are mistakes like this (odd number of beats). Unless the composer is there to explain what they want we have to decide how to interpret the writing. Sometimes when the composer shows up for the performance of a new work time is wasted explaining things that should have been taken care of in the engraving.

Speaking as a LilyPond user, I’m glad to see the correction below for the bit of FUD about needing to learn Scheme in order to use LilyPond. I hope that rumor will disappear eventually. I agree with you that LilyPond is easier to approach if you’re already used to typing text symbols to achieve a graphical (or non-text) result (i.e. prior programming or LaTeX experience). But the beginning LP tutorials — i.e. \relative c’ { c4 c g’ g a a g2 } for “Twinkle, twinkle…” — make it pretty clear that note entry itself is far, far simpler than programming. Probably most of your readers can guess what the { c4 … } bit means without even reading the tutorials!

Anyway, I’m not here to advocate for LilyPond. I’m more interested in seeing a new tool emerge that can issue a real challenge to Finale’s miserable, awful, hasn’t-improved-much-in-some-twenty-years-now (non-)handling of graphical collisions. It’s simply an embarrassment that the most widely used scoring package in the world can’t get anywhere close to proper placement notes and accidentals in music with multiple voices on a staff, without user intervention. But that will never change until a rival package threatens to win over their user base through better default layout.

If you guys can crack the collision-avoidance problem, I’m all for it (though I’ll probably continue to use LilyPond for other reasons — the main ones being the human-readable, plaintext format, and that format’s compatibility with version-control systems).

It all looks good to me, Daniel.

I’m unlikely to use many of the more ‘unorthodox’ functions, but pleased to read about them all the same.

The barlines thing is dear to my heart.

And although fond of Sibelius 7 (despite the odd wart), I am fascinated by the idea of approaching the ‘blank page’ from an entirely different direction.

I’ve recently been pontificating to postgraduate students here on ‘intuitive and/or deliberate’ modes of creativity, and I fancy from your comments that the new ‘Steinbach’ software might be heading in a direction I would find congenial.

.

Probably way down your list, but it would be wonderful if the available images included some of the things that are needed for early music, eg prolation signs (some were present in Sib 6, but others were wrong and others were missing), clefs in the style of early printers, etc. Also a function to add ranges to a prefatory stave simply by having the program do the analysis would be a big timesaver. Thanks!

@Stephen: Bravura already includes a diverse set of prolation and mensural symbols. Please take a look at the SMuFL document and let me know if you spot any glaring omissions.

Sounds like some amazing work is being done on this application. My main query in regards to its final release is the attention to accessibility the developers of the GUI are making? As a blind composer myself, notation software is notoriously difficult to use resulting in methods such as Lilypond being a last resort. Although don’t let it be misconstrued, as I believe Lilypond is a dynamic and feature-rich text-based engraver, but the matter of choice for people such as myself has been limited.

@Hayden: It is absolutely our goal to make our new application accessible for blind and visually impaired users. There are some hurdles to clear in order to achieve this, to be sure: we’re building the GUI parts of our application on Steinberg’s existing GUI framework, which is used for all its other applications (except for Wavelab), and currently there are some serious limitations in the framework’s accessibility support, but it’s something we are going to work on with our colleagues in Hamburg, and hopefully we will be able to address those limitations before our initial release, though I can’t make any firm promises at such an early stage of development.

Thanks Daniel for the update,

I agree on imputing the sharps/flats before the note, but not entirely agree with the octaves. Thinking in melodies, most o of the time the next note will be in the same octave, so for fast input having to decide the octave before could take some time and make the whole process slow.

As I told in a previous post, could be great to have a program where music could be scored like traditional notation and also in a publishing layout. Having the possibility to detach music from it’s original place while keeping the playback and simply press a button and see the score as a continuos track (king like the panorama view). Of course this could become a mess on the layout, to avoid this I suggest using big letters (just for organization and not for printing) or number like the ABC…AA BB CC…. AAA or something similar.

This would be great for composers with different ideas about music writting and also for educators making music methods or exercises. I remember when sibelius came with that huge list of exercise sheets, unfortunately for able to do that from scratch, users had to a lot of tricks…

looking forward for the next info updates

@Ricardo: Perhaps I wasn’t clear about octave selection, for which my apologies. The program will make a default choice for the appropriate octave for the next note based on proximity to the last note you input, but if you know that, say, having entered a C you want the next note to be the G above rather than the G below, which the program would choose automatically because it’s a fourth away rather than a fifth, you can influence that choice before you input the G, rather than afterwards — though you can also adjust the octave afterwards, of course, if you prefer.

thanks, I think that way it’s great!

Thank you for that. The inability to override the default octave by proximity in Sibelius (unless I have missed something) is possibly its most annoying and time-wasting shortcoming.

On this point Daniel, it would be great if the software would give the 5th above rather than the 4th below for instances when the 4th below would take the note out of the compass of the instrument.

By far my favourite Sibelius feature was the ability to customize shortcuts, it made the transition bearable… I hope your software includes this “essential” feature.

@Claude: Yes, it’s a safe bet that it will be possible to customise keyboard shortcuts in our application.

I’m excited that some of the freedoms which SCORE users used to enjoy are to be employed in the new software. Having total control over the placement and exact shape of every item was a luxury, which, alas, came at a price – a steep learning curve, a severe playback limitation, and a page by page, instrumental group by instrumental group structure, which meant that second thoughts were almost out of the question.

I’m anticipating that the new program will be a world beater (no pressure then!)

We have a symbol we use for the opposite occasion. When you absolutely must not look up (the conductor is emoting, possibly). It’s the normal eyeglasses, but with darkened lenses. My apologies to those of limited or no sight. Just a joke we use.

Thanks for providing this account. I would like to suggest a symbol to use which I doubt is yet in any software. It’s a little icon of a train derailing. It could be used in place of the pair of glasses. Sounds funny, but what’s wrong with that? I’d use it.

Hey Daniel, thanks for this interesting and exciting news. I’m looking forward to use and to check out the upcoming new scoring program.

Best Wishes

Bernhard

Hi Daniel,

great new info in your post !

Thanks for pointing out, that Finale- or Sibelius-Users (and others) need to be willing to learn a new software – as your team is made mostly built on Sibelius-Coders, some people might think that you “re-invent” the same thing again?!

Well, I did not … 😉

Here are some thoughts on the SMuFL and Bravura development:

I think it is a great idea of having a unicode-based, general and standardised key chart for music notation running on Linux, Windows, Mac, Android, iOS etc. either way- it is a great approach!

The Bravura Font as a first result of this is looking great already (the thickness of the stems and heads is very good to read)!

The only thing I am afraid of is:

There is so many different ways of music notation (reaching from medieval “Neumen/Tropen/etc.”-stuff, passing by a “Broadway/Hand-written-Look/Jazz-Type-Chords”-appearance, going on to the “contemporary-composers-with-special-ideas-how-to-touch-an-instrument”-issues …)

As Jazz notation is on of my personal subjects, I would like to point out only two aspects:

Already today with the given two major apps, there is so many ways typing symbols for jazz-chords like a simple chord like “Cj7” which would be the same as “CMaj7” as well “CΔ”. Things become difficult with chords like “Fj#11”, “Am7(b5)”, “A7#5b9”

Not even to speak of the fingering patterns or tabulatures for guitar players…

I was thinking that it might be too hard to combine all these needs in only one character-map?!

So maybe it would be good to split-up the font family ? (Having SMuFL for Jazz or Classic could resilt in fonts like “Bravura-Old”, “Bravura-Jazz”, “Bravura-Classic”, “Bravura-Modern” etc.) Of course the character-mapping has to be generally the same and respected, so that interchange-ability is possible at all…

Daniel, please get me right: I love the idea of SMuFL!!!!!!

How many Exclamation marks are allowed… ? ;-))

I just hope that it is not going to end up in a complete chaos.

(As you mentioned the map is already filled up with a lot of glyphs…)

That is just my thoughts;

And a very last thing: accidentals must go before the note: #C!

I would even say that music instructors and teachers should get used to call the note a “sharp-C” and not a “C-sharp”; but that is a different topic.

Best greetings and keep going!

Steffen

@Steffen: Thanks for your comments about SMuFL and Bravura. Bravura itself doesn’t need to provide glyphs for handwritten-style music or other different appearances, since that should be the job of other music fonts. Bravura is a SMuFL-compliant font that has a traditional, engraved appearance; hopefully there will be other SMuFL-compliant fonts available in the fullness of time that have different appearances, including one that has a handwritten look.

Regarding chord symbols, SMuFL only encodes the special symbols required for chord symbols, i.e. the circle and slashed circle, triangle, plus and minus, because scoring applications are free to implement chord symbols however they please. For our application, for example, the plan is to allow the user to choose any text font on their system for all of the letters and numbers in a chord symbol, and then use just the accidentals and special symbols as required from the music font.

Good Lord! A picture of the keys and hammers of a Musicwriter and a mention of Notaset transfer sheets! What nostalgia! That’s how I used to engrave (plus text by IBM Selectric) midway between the 60s and 70s! Thanks for that “blast from the past,” and filling us in on everything that’s going on today. 🙂

I’m also curious to hear about whether you expect to have the program work with Cubase natively. While many of my peers in the film world use their sequencer to create parts, I find it very limiting. The flip side would be having the notation program be able to handle enough MIDI to really provide acceptable performance. Looking forward to hearing more on this topic, and I understand that may be farther off.

@Richard: In the long-term we hope to integrate with Cubase, but it’s not clear exactly how that will happen. We certainly want to create compelling reasons for you to use our scoring program together with our sequencer, but exactly what that means for our first version and how it will develop over time is not yet 100% clear. Sorry I can’t give you a more specific response!

I will like to share a little of my needs about music notation. I have tried many notation software demo and still looking for easy to work options.

One of my needs is the use of any clef moved to any line or space. I use this manually to practice with my students the concept of “movable do”. I usually have to write clefs by hand.

I gave also a composition class where we try to find the tendency of a piece by counting the frequency of a note being used and for how long. There is a java program but then I had a long process to transfer the piece into that system.

I also needed the note counting system for my arrangement for bells. When I know how many times a bell is played, I can assign them in relation to skill and experience of ringer.

While in school I wished I could have an special kind of staff/notation (like the percussion staff or something like that) to write “Umbrella analysis” within the notation software …

I have found very useful the way Notion software adds an Ntempo staff to tap the tempo of a live performance.

An I am still looking for the old times when Music Printer Plus allowed me to play backwards !!! It is just great to be able to train the ear to hear progressions and retrogressions and re-arrange or re-compose a piece just by changing the order of the relation between the chords.

With sadness I saw Sibelius changing by using more and more libraries. The best version to me that really optimized the computer power was version 4. I believe that just because processors and the lower price of memory and hard drives are available, we have been bloated with unused code. I may be wrong, I am not a programmer, but for certain unknown reason it feels like that.

Every musician has his own personal preferences and needs. To create a software that fits the creativity of each one may require … extra creativity !!!!

Good luck !!!! Be Extra Creative !!!

For things like note counting, I would imagine that SCORE will (hopefully) have some kind of scripting interface similar or better than ManuScript in Sibelius so you can implement your own little nichey features like that.

Daniel, what kind of scripting will be implemented in SCORE if any?

@Kevan: For clarity, SCORE is not the name of our in-development application; SCORE is one of the longest-lived music notation computer systems, having its genesis in the 1960s at Stanford University. It’s still under development today by its progenitor, Leland Smith, and you can buy it from scoremus.com if you’re so inclined. Our new application doesn’t yet have a name — but it will have in-depth scripting support via a built-in Lua interpreter, so you’re right that it should be pretty simple to write scripts to do things like count the number of instances of individual pitches.

As a developer specialized in Python, I have nothing against Lua, but I consider Python a much more powerful language, with more batteries included, and I wonder what the cost of supporting Python would be for you…

By the way, developing a music score editor is a dream job for me.

@Nando: There was a lot of discussion about which scripting language we should work with in our application, and Python was certainly a front-runner, since a couple of the developers on the team are very familiar with it, but in the end we decided we would stick with Lua, which is used in other Steinberg products already.

Thanks for that. I’m just gonna keep plodding along with Sib until this one comes out.

And forgot to add another feature !!! Harmony Assistant ability to have a simulated voice helps making “minus one’s” for church choirs !!!

@Mephi H:

I hope that it won’t be frowned upon if i mention here that in LilyPond you can place any clef at any position (be it on a line or on space). Also, it should be quite easy to count notes using a simple script, thanks to LilyPond text format.

best wishes,

Janek

Actually, there is a frown in the making at least on my face.

“To be clear, though, I’m not proposing that this should be the main way people input music into our application, but it might be useful for e.g. accelerating the input of music via a Lua script.”

I’m not sure if the world is waiting for another and yet another music input language. Why not using one of those that are already there, I mean as a basis of a lua scripting engine or LaTeX-like input use cases!?

Sounds exactly like some features that Columbus Soft’s scoring app PriMus offers. Did you already have a look at EMIL, the music input language for lua scripting in PriMus?! you should do that.

Or chose one of the more familiar ones like abc, plain and easy, lilypond, mup, guido…

Regards, Carsten

@Carsten: I anticipate that the scripting support in our application will be sufficiently rich that if somebody wants to write a parser for ABC, Plaine & Easie, LilyPond, mup, Guido, or indeed EMIL, they’ll be able to. The specification of a text-based input method for our application is simply a means to an end, a way of experimenting with the keystrokes required for alphabetic (step-time with the computer keyboard) input while we are designing the application, and if it happens to be the case that this also provides a convenient way to encode input instructions in text, then that’s useful too. The disadvantage of using one of the many other text-based descriptions is that it will have little or no commonality with the way our application’s interactive input method works, so learning (e.g.) the LilyPond syntax won’t help you much with inputting directly into our application in the normal way.

As a musician and aranger, and beeing visually impaired at that, I find it a challenge to do notation on a graphic based envoronment. I love lilypond, but I cannot hear if I’m entering it in the right octive or now until I play it bac, same with transposition of let’s say a horn in F or a b flat claranet. if this text based method can be made accessible and I’m able to print out professional looking arrangements I and all of this from a mac using voice over I’ll be very very happy as I can get back to work on aranging one of my favorite christmas songs as a surprise for one of my profs at my school. I look forward to reading part 3 and if possible when this thign is released testing it for accessibility with voice over. Good job on the post.

Daniel, glad to read your gathering all sorts of information on fonts and looking into other methods of input. That kind of thoughtfull approach can insure that the new application will be rich with choices for the music publishing industry. Thank you for your diligence. Tony of http://www.Mmhcmudicpuplications.com

I hope we will have a notation software both for experts and beginners, both for sophisticated engraves and sophisticated MIDI functions. Steinberg Cubase is the cutting edge MIDI software, just improving its notation functions maybe is the simplest way.

Best wishes!

Agreed. I’m a visually impaired arranger and would love to have a way to successfully make good looking choral scores for my women’schorus I’m in. I saccessibility, that is the ability to work wiht voice over on mac osx beeing looked in to? I hope so as this woudl be easier then lily pond for me anyway.

Take care.

Excellent Daniel! A fascinating glimpse. Some talk here about Lilypond and Score. My experience of those, as a composer rather than engraver, was not great since I found myself resorting to pencil and paper and Sibelius for initial composition because it was impossible (for me) to think ‘through’ those programmes in the way I could with Sibelius (and even, but to a lesser extent, Finale). Not exactly the point of the exercise!

An exciting and agonising wait!

All the best

Pete

I noticed your mention of Sagittal accidentals, and I wonder what other non-standard or “reform” elements you might include in your software. Might I also refer you to my work in what I term “quintuplous meter,” or five-to-a-beat notation. Here’s a link to a poster that I presented at the College Music Society conference in Minneapolis a couple years back that outlines what I’m thinking: http://www.martiandances.com/uploads/1/6/0/1/16019142/qmeter.pdf

Best wishes for a successful development of what looks to be an excellent product!

@Matthew: Thanks for the link to your poster. I hope you won’t be offended if I say that we would need to wait for your proposed system to catch on and for there to be a lot of demand for our software to support it before we would spend a lot of time implementing direct support for it. However, our aim is to make our software as flexible as possible, so it should certainly be possible for you to get the desired result in our application, even without direct support for it.

Sorry if this was already requested; my big ask would be for multiple voices on a single stave (at least 4) to either automatically or easily organise themselves horizontally to avoid clashes eg with intervals of a second.

That and *try* not to make the new programme so new it only runs on the very latest OS versions.

Stephen

I hope that the new scoring application will have the possibility to use time signatures with 3, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 12 and 15 as denominator. I compose sometimes very complex polymetric and polyrhythmic music and this kind of times signatures makes it much easier to get a clearly arranged score.

Best wishes,

Michael

@Michael: It’s a safe bet that you will be able to work with time signatures with non-power-of-two denominators in our new application.

Very happy to see microtonal symbols included in Bravura; particularly glad to see Ezra Sims’ accidentals included, as I use those in my composition. Sib 7 can play back microtones using MIDI messages – will this capability be part of your new application? Using Sib 7 happily, don’t plan to ever “upgrade” – looking forward to your new and better creation!

@James: Yes, our hope is that microtonal playback will be included in our application, at least for schemes based around equal divisions of the octave.

Thanks to that! Please make microtonal xml import possible (i.e. from Open Music by IRCAM). If somehow possible up to 12th tones. I would pay a fortune to get a notation software that can deal with that. Notability Pro is good at it up to 8th tones. But dealing with scores is to complicated. Right now I’m dealing with finale and workarounds. Start hating it more and more.

As a wannabe notation software designer I find this blog extremely interesting. And as I am very new to the field would you possibly point me to sources of literature, if any, that I could study in addition to studying source code? This area seems to lack much documentation. Thanks so much for your work and your inspiration.

@Donald: There aren’t really any books devoted to the design of notation software specifically, but of course there are many excellent books on software design and on music notation and engraving.

It’s probably overstating the case slightly to say that there’s only one book you need on engraving these days, but if you only do buy one book on engraving, it should be Elaine Gould’s Behind Bars. There are lots of other excellent books, including Gardner Read’s Music Notation, Kurt Stone’s Music Notation in the Twentieth Century, the little Norton pocket dictionary of music notation, and others besides, but all of those books are really only recommended to provide a counterpoint (no pun intended) to Gould. If you’re looking for books that cover commercial copying for film and TV etc., then you should try and find Ted Ross’s book The Art and Practice of Music Engraving, and Clinton Roemer’s book The Art of Music Copying. You should also think about Adler and Blatter for orchestration, and Fred Karlin’s book On The Track for an introduction to film scoring.

For software design, take your pick! A recent book we’ve enjoyed here is Lukas Mathis’s Designed For Use. I enjoyed Joel Spolsky’s User Interface Design for Programmers, though it’s a bit dated these days. I have also found books that are not directly related to software design but rather to good design in general, such as Donald Norman’s The Design of Everyday Things full of valuable insights that I have (hopefully) been able to apply to the software I have designed over the years. A former colleague of mine also recently forwarded this collection of online writing to me, in which you might also find some gems.

Hopefully that little lot gives you some leads on resources that might be of value to you.

Thanks for your great feedback. I’ll look into these. I’m familiar with Norman’s book but the rest are new to me. The big issue, of course, is how to represent the data. But that is the stuff of secrets so I shall have to muddle on myself. Thanks again.

I would like to suggest a feature. The ability of scripting in a program like this it’s a must because the programming team is not able to address all the requests from different users. Although most of the users are unable to do scripting. So I would like to ask you to include a small visual scripting wizard to make simple scripting, this would allow users to program a new function without having to write a single line of code.

Panel 1

Input: from file, whole score, selection

Panel 2

What to do: notes, rhythms, dynamics, articulations, symbols, text, layout etc….

Panel 3

Where to save: change the score or new file

The panel 2 could have the possible to add several options

For example if I wanted to change the notes and e dynamics, the user had to set up what to do with the notes and what to do with the dynamics

This is the approach used by apple

http://support.apple.com/kb/HT2488

I’m really looking forward to your notation software

It’s ALL great news!!

Thanks Daniel!!

Does this new package have a title [working, code-named, internal, or otherwise] at this juncture?

@The Antique Harmoniums: It has an internal codename, but not a proposed go-to-market name just yet.

How wonderful it would be if the new application worked with Cubase in such a way that the tools from one application were available to edit content in the other, similar to the way in which one can click on a bitmap in a word processor and have another application open for editing.

I would also love some innovative tools for the graphical representation of live midi.

Hi Daniel,

I just discovered this blog and am excited to follow the development of this new software! Like Donald Hamilton above, I am working on a pet music notation software project, so I am very interested in learning about the choices made by you and your team (I have an idea what kind of design challenges are involved!) I understand that most of the code-level decisions are probably confidential, but I would absolutely enjoy reading a blog post that digs down into some of the inner workings of your application, if you get a chance! If not, I’ll be happy reading the rest of your higher-level progress reports as well.

I also want to offer my thanks for freely releasing the beautiful Bravura font, it is going to be very helpful!

Best of lucks with the development effort! I look forward to see its result!

Is this the right place for feature requests? I have several.

@Stuart: It’s probably better if you send me an email if you have a lot of requests.

What is with all the Lilypond users (one myself) spamming this blog? If you want to extoll the virtues of Lilypond this isn’t the place.

Thanks for the update Daniel.

Can we PLEASE PLEASE PLEASE PLEASE get microtonal playback? The sagittal notation is the best news I’ve heard all year!

Really interesting. I was thinking about language in general just yesterday. In English, we put the adjective first, then the noun. In French, the noun is first and then the adjective. The white house, the house white. So in music we might have the flat B, or the B flat. Looking at printed music, we indeed visually see the flat B when scanning horizontally from left to right. This has me wondering about languages that read from right to left, is their music also written in reverse? I digress into ignorance.

So your step-entry decision is to go with what is visually seen on the page, and to avoid hearing the wrong thing before hearing the right thing. When reading, I disagreed with you until I thought about things in the way I have written so far.

Your mention of bar lines also caught my notice. I am so very annoyed with scoring applications automatically giving you a number of bars to work with at the outset, with a double bar at the end, and great initial confusion as to how to change that number of bars while entering notes. I would much rather have no bar lines at the beginning and add them as I progress. I would also like to be able to enter too many notes into a measure and then split that measure, assuming I’m adding music into the middle of a score and have effectively added an extra measure in a free-form manner. The refusal of a scoring app to let me add too many notes into a measure infuriates me. Ideally, such rigid behavior should be able to be toggled on and off, along with a feature to check for mistakes in rhythmic measure length.

@Jim: The neat thing about Dorico is that you can indeed work with no barlines, and then add them later on, either in a regular pattern by adding a time signature of some sort, or simply by creating them wherever you want them to appear.

I was also thinking about my current DAW, Logic Pro X. It would be lovely, for me personally, to have a DAW built around a scoring paradigm. There would be a score view and also a piano roll view. In the piano roll view there would be a hollow rectangle representing the “quantized” notes as written in the score and the colored filled in portion of a note would be the actual performed duration. One could edit the performance by adjusting the colored length, and one could edit the score by adjusting the enclosing hollow rectangle — thus, one could adjust the performance and/or the score from the piano roll view. If one were to adjust things in the score view, the piano-roll information would be “destroyed” and become fully quantized.

So that’s how I wish things would work, and I would prefer that Dorico and Cubase were one program, where Dorico is “merely” an important view of the Cubase DAW. Anything else is a kludge when trying to use them together. Put another way, Dorico should start as a scoring app and grow into being a proper DAW.